Featuring the Doe Network.

By Lane DeGregory

Saint Petersburg Times

November, 2003

A skeleton is found in a citrus grove. A forensic sculptor gives the bones a likeness. But a mystery lingers.

When Tara Exposito disappeared last November, she left behind her mom, Rebecca, holding 15-month-old Isaiah; older sister Angela, 16, right; plus younger sister Julian, 12, and younger brother Michael, who just turned 10..

The skeleton was scattered across a citrus grove in East Hillsborough - a femur, a finger, a jawbone nestled in a tangle of highlighted hair. Sun had bleached the bones. The skull lay on its left side, tilted toward a rotting orange.

Fragmented remains of a life, now barely recognizable as human.

Detective Dale Bunten arrived on the scene Jan. 8, a day after a young man stumbled across the skeleton and called the police.

Bunten called in the medical examiner, who measured the size and shape of the skull and the growth plates in the pelvis. He said the bones belonged to a white female, age 12 to 17. She had been dead for at least six months, maybe as long as two years.

"Neighbors told us that grove hadn't been worked in more than a year," Bunten would say later. "But you have to wonder how this person was out here for that long, and no one discovered it."

Finding only bones is unusual. So is finding the remains of such a young girl. Bunten had no idea who she was or what she might have looked like. He had no tissue, no fingerprints. He gave her the usual police name for an unidentified female: Jane Doe.

It would take almost a year of steady, determined work for Bunten to learn her identity. What he discovered would solve a year-old mystery and break the hearts of a family in Pinellas County.

Jane Doe turned out to be somebody after all.

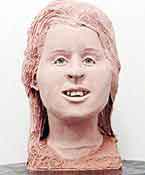

The real Tara Exposito, left, and the clay head. “The cheekbones were right and the lips and nose were there. But the smile was way off,” said Tara’s mom, Rebecca.

Process of elimination

Bunten has worked for the Hillsborough County Sheriff's Office for 19 years, guarding prisoners at the jail, investigating domestic violence and stolen cars. The day before the skeleton was discovered, he began his new job as a homicide detective.

This was his first case.

He started by sending an alert to every law enforcement agency in the Southeast. He posted pictures of the skeleton, along with the girl's assumed age and race. He scanned runaway lists, searched missing persons Web sites, called Florida's network for missing children.

Soon, he had a list of 60 teenage girls who had disappeared across the state in the past two years. He hunted down their photos and compared them with the size of the skeleton and the mass of highlighted hair. He ruled out the African-Americans. He excluded heavy-set girls because the medical examiner thought Jane Doe was thin.

He got calls from cops as far away as Georgia. One officer called from Gulfport, an hour's drive across Tampa Bay. But the girl he was searching for had been missing for only two months. The medical examiner said this skeleton had been out there a lot longer.

An uncommon smile

Near the end of January, Bunten searched the citrus grove again. Thirty men, shoulder to shoulder, combed the sandy trenches under the orange trees. They found more bones, almost all of them this time.

They didn't find jewelry, a purse or clothes. Bunten had no way of knowing how the girl had gotten to the field: willingly or unwillingly, dead or alive. The medical examiner hadn't found any nicks on the bones from bullets or knives. Without blood or organs, it was difficult to do toxicity tests, almost impossible to determine how she died.

In February, a forensic dentist X-rayed the skeleton's mouth. Whoever she was, the girl had unique teeth: crowded, overlapping, protruding eye teeth on both sides.

"And she'd had no dental work done, which was highly unusual," Bunten said. "No fillings, no braces. That makes it so much harder to match."

In March, a forensic anthropologist confirmed the medical examiner's findings: the girl was younger than 17 and probably weighed about 100 pounds.

In April, Bunten sent a leg bone, a tooth and some hair to the FBI. Maybe the skeleton's DNA would match something in a missing persons database. The FBI said they would have results in four to six weeks. But summer slid by without any new leads.

Then Bunten heard about a sheriff's deputy in South Carolina who specializes in forensic art. The deputy, Wesley Neville, sculpts clay onto skulls, coming up with an educated guess at what the person might have looked like.

In late July, Bunten sent Jane Doe's skull to Dillon, S.C.

An eerie likeness

"I seldom get such a young girl," Neville would say later. He's been doing forensic reconstructions for 13 years and has helped solve cases from California to Germany.

"The younger it is, the more they get to you," he said. "Plus I have an 8-year-old daughter, so this one was really tough."

Neville started by mounting the skull on a steel pole, so he could spin it. He noted the height of the brow, the width of the nose cavity, the breadth of the mouth.

"The first thing I noticed was this girl's unusual dental work," he said. "Normally, I make a closed mouth. I try for the face not to have any expression. But with this one, I knew I'd have to do an open mouth, a sort of smile. Because that's what people who knew her would recognize."

Neville photographed the skull from all angles. He measured the gum line to calculate how wide the girl's lips would have been. He wrote that her mouth was long, her eyes set close together. "And she had a very unique nose, a lump coming down off the bridge, but rounded on the tip." How could he tell that from looking at a hole in the skull? "You study the nasal spine, you can see the dip coming off the brow ridge," he said. "From that, you can calculate the length and shape of the nose."

Next, he figured out how much flesh would have been on her face, how round her cheeks would have been, how deep her eyes must have been in their sockets. He glued 32 tissue markers onto the skull - eraser-size rubber discs, numbered and plotted on graphs.

He sculpted clay over those markers, contouring the eyebrows, cheeks and chin. "I start at the top and work down," Neville said. When the face was finished, he added doll eyes and hair. He chose hazel for this face, based on the blond-brown nest of hair found at the scene.

When he finished, Neville photographed the head and made a package for police.

He mailed the report to Bunten on Aug. 7.

The next day, Neville was browsing through missing persons Web sites when he saw the girl he had just reconstructed.

Her face was smiling at him from the screen: close-set hazel eyes, a nose with a lump near the bridge, crossed teeth.

"I couldn't believe it," Neville said. "I started printing out pages to show my supervisors."

Neville called Bunten and told him about the Web site. He told the detective that his package would be arriving soon. But in the meantime, he should check this out:

The posting showed a white girl from Gulfport. She was 14 years old. She had blond-brown hair. She stood 5 foot 2 and weighed 100 pounds. She had been missing since Nov. 6, 2002.

Her name: Tara Exposito.

"Tara, please come home"

Bunten ran her name on Google and came across an article in the St. Petersburg Times. In January, the same week the skeleton was found, the paper had run a story about Tara and her mother's efforts to find her.

Tara had last been seen after school on Nov. 6, somewhere between Boca Ciega High and her house on 14th Avenue S. Her sweater was found in her driveway. Her hair tie was in the grass, down the block.

Police thought she had run away. She'd run away before. But this time she didn't come back. The article, called "Tara, please come home," told of the family's anguish at not having her home for Christmas.

Bunten called Sgt. Ron Howeth of the Gulfport Police Department. Howeth had been searching for Tara for nine months. He kept her photo on his desk. He called her mom every week.

In January, Howeth had called the Hillsborough County Sheriff's Office asking about the skeleton. But the medical examiner said the remains had been around at least six months. And Tara had been gone only eight weeks by then.

Environmental factors sometimes cause remains to deteriorate faster than usual. The Florida heat and sun, along with animal activity, can age bones quickly, the forensic artist explained. It was possible, Bunten said, that the bones could be hers.

Tara had hazel eyes, a heart-shaped face, honey-blond hair that fell past her shoulders. She liked listening to Creed and No Doubt, playing football on the beach, singing Jewel songs to her baby brother until he fell asleep. She was small but scrappy, a fighter, a "canary with an alligator mouth," her dad once said.

Tara was the second daughter of Rebecca and Shawn, who both grew up in Gulfport. Rebecca processes loans. Shawn used to lay carpet before he hurt his back. Since Tara disappeared, he'd been in and out of jail several times: for threatening his wife, kicking in the front door and assaulting his oldest daughter while she was pregnant.

From the beginning, Tara's dad was sure something had happened to her.

Her mom insisted on holding out hope. She put up fliers, interviewed friends, tried to track down her daughter. She bought Christmas presents for Tara and put them outside her bedroom window in case she was hiding somewhere in the dark. Seven months after Tara disappeared, her mom baked her a birthday cake, just in case.

Seen around town?

When Bunten got the package with the reconstruction photos, he drove the hour to Gulfport and showed them to Howeth. The Gulfport detective agreed that the face looked a lot like his girl.

That afternoon, Aug. 12, Howeth took Tara's records to the same forensic dentist who had X-rayed the skeleton.

The teeth were almost identical, the dentist said. A 99 percent match.

Howeth and Bunten drove to Tara's house to tell her mom.

"They made me look at pictures of this clay head. It was awful. But it did kind of look like her," Rebecca Exposito said later. "The cheekbones were right and the lips and nose were there. But the smile was way off.

"It was very, very creepy."

Rebecca refused to believe those bones belonged to her daughter. People kept saying they thought they'd seen Tara around town. Ninety-nine percent wasn't good enough.

"Because the mother was so upset," Bunten said, "we agreed not to make a definite identification until we got the DNA results back."

"I smacked her"

For the next three months, Tara's mother waited for the results at home. Her father waited in jail. He was in for violating a restraining order meant to keep him away from his wife.

Last fall, Shawn Exposito was charged with child abuse after he slapped Tara across the face.

"She wouldn't get out of bed. She wouldn't go to school. I took her computer and her phone and her TV out of her room," he said last week at the Pinellas County Jail. "But she still wouldn't budge. So I cut off her air-conditioning. She jumped up cussing, called me everything but a white man. So I smacked her, just my open hand. That was shortly before she came up missing."

Before that day when he slapped Tara, "I hadn't put my fists on my children in five or six years," Shawn said. "Maybe that's what was wrong with them."

Shawn is bipolar. He's supposed to take medication for schizophrenia. "And I have a terrible drinking problem," he said. "But that's no crime. I haven't been convicted of a felony in more than 10 years."

Now, he said, "The detectives are grasping at straws. They're looking at me. I'm their chief suspect."

Tara’s father, Shawn Exposito, is in the Pinellas County Jail for violating a restraining order meant to keep him away from his wife. He says of his daughter’s death: “They’re looking at me. I’m their chief suspect.” Detectives have named no suspects in Tara’s death.

Later that day, Nov. 14, Bunten and Howeth said they hadn't named any suspects in Tara's death.

They hadn't even confirmed the body was Tara's.

A knock on the door

Three days later, on Monday night, the detectives went to see Tara's mother.

It was almost 10 p.m. Rebecca's other children were sleeping. She was getting ready for bed, wandering around the dark house, wondering, as usual, whether Tara might come home that night.

There was a knock on the door. When she saw the look on Howeth's face, she knew.

"I was waiting for her to show up," Rebecca said, starting to sob. The policemen bowed their heads. They had been waiting and hoping, too.

More than a year had crawled by since Tara disappeared.

Ten months had passed since that skeleton was discovered.

"At least we have some closure for the family now," said Bunten, who had received the DNA results that day. "No matter how sad it is, you need to know."

On Tuesday, Howeth closed Tara's missing person file. And Bunten changed the name of the Hillsborough case file from Unidentified Remains to Suspicious Death. Police still aren't calling it a killing. And they're not naming any suspects. "But we're already doing a lot of backgrounding," Bunten said. Now that police know who the victim is, they know who to start talking to.

"A 14-year-old girl turns up dead in an orange grove," Bunten said. "We're going to find out how she got there."

* * *

A memorial service for TaraExposito will be held at 2 p.m. Dec. 6 at theFamily Fellowship Center, 5475 54th Ave. N in St. Petersburg.